By Ernest Granson

New concepts, technologies and disruptions are constantly bubbling to the surface of the industrial landscape. Blockchain could fit into either one or all of those categories, although it’s not necessarily new, having been introduced a decade ago as the underlying platform for Bitcoin.

For Elena Dumitrascu, co-founder and chief research and technology officer at TerraHub Technologies Inc., blockchain’s current status as an acceptable technology in food production or any other sector, for that matter, is a natural progression.

“I was just starting my career when an e-mail appeared on the scene as a tool in business; now you can ask, ‘How did we ever do without e-mail?’” she says. “Smart phones, texting, calling Uber for a ride – none of those happened overnight. Companies that are paying attention to these new options will be in the winning seat in comparison to their competitors.”

The fact that no one has full ownership of the full data contained within blockchain makes the technology extremely useful in many industries, including the food production, distribution and sales sector.

According to Dumitrascu, it’s also the difference between the current food tracing method using scanning technology and employing full blockchain network.

“In the case of tracing food from farm to retail sales, unlike information that is scanned from a bar code and stored in a single system, blockchain allows all the various parties involved in the distribution process to have a direct copy of every step and activity which that particular item has gone through,” Dumitrascu says. “Currently, if you take a grapefruit and scan the bar code, by whom is the information stored? Is it the farmer who grew it, is it the store? In blockchain, there is no single party which stores that information, and no party can singlehandedly modify the record.

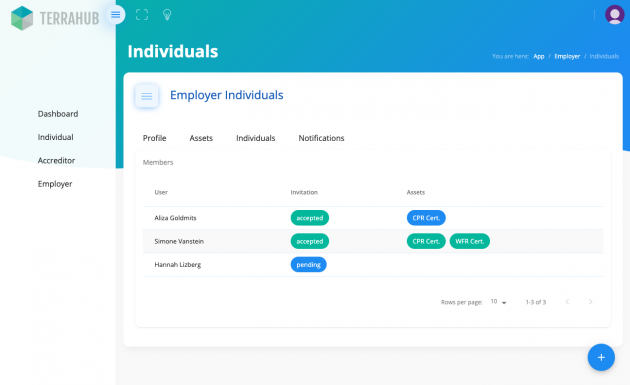

The blockchain interface in operation.

“As it gets captured, it gets shared with all relevant stakeholders: the farmer, the trucking company, the distributor and the store,” she continues. “And, it happens almost instantly. All impacted parties receive an instant copy of the information. So, in the case of tainted lettuce, because no one party has full ownership of the data, the information about the lettuce can’t be changed; which would prevent tainted food being accidentally placed back on the shelf.”

With the technology currently being used, if someone in the distribution chain wants to trace an item, such as where it originated or the date it entered the chain, there’s no guarantee that the information will be accurate or correct because someone along the chain can make a change. In blockchain, a change can be entered in the system, but the edits are visible to everyone connected to the system.

With the technology currently being used, if someone in the distribution chain wants to trace an item, such as where it originated or the date it entered the chain, there’s no guarantee that the information will be accurate or correct because someone along the chain can make a change. In blockchain, a change can be entered in the system, but the edits are visible to everyone connected to the system.

However, as Dumitrascu points out, designing a blockchain system is not as simple as allowing all the information about a specific item to be entered in the system and made available to everyone involved in the chain.

“You have to be careful what you share and why you are sharing it,” she says. “For instance, knowing the price rate that has been arranged between you and the farmer could be considered an advantage for someone else along the chain. You wouldn’t want that information to be shared. But a piece of information, such as whether the food item is certified organic, could be accessible to everyone. From a business standpoint, not sharing pricing information makes sense. On the other hand, you don’t want to that kind of system to become a monopoly system or create an antitrust situation.”

Blockchain does allow for the rules to be different based on the parties involved. The system can be designed so the farmer, the transporter, the port authority or the final buyer have only segmented access of the full information in the system. Where a grapefruit was grown might be a useful detail for the trucker or the buyer, it may not be necessary to make that information accessible to everyone along the chain.

Upon face value, implementing blockchain for food production makes sense, but, by no means has the technology been accepted in general by the food production sector. And so far, according to Dumitrascu, there’s a low acceptance level in the industry.

“You have to remember, this type of technology has only been around for a relatively short amount of time,” says Dumitrascu. “It’s difficult to develop a complex technology for industry adoption in such a short amount of time. There are so many questions and scenarios that have to be considered and resolved before it becomes an industry standard. We’ve done pilots with members of each industry category to have them evaluate if using blockchain improves their logistics results. We’ll ask them, ‘Do you get paid more quickly, are there less disputes, do you have better understanding of your inventory levels?’”

That low acceptance level is not a technology problem, Dumitrascu emphasizes. It’s an education problem, and that is where TerraHub enters the picture.

“The magic we have at TerraHub is that we’re not only technologists but also business people,” she says. “We can help businesspeople fill in those gaps. Working with C suite executives and board directors, we apply blockchain technology to real life examples. For instance, we’ll point out that, ‘Today, you’re spending this amount of time connecting with these 50 documents when you could reduce that time by accessing the same information such as reconciliation or audits, the works, from one source.’”

While Dumitrascu is educating the industry about incorporating blockchain into food production at the local level, her involvement with the technology has already been national and international in nature.

Dumitrascu and John Dugdale, co-founder and CFO of TerraHub Technologies.

She became involved during her 15 years of experience in the oil and gas industry when, as co-founder of Caledonia Solutions Inc., she was involved in the conversion of the hazardous goods sector from paper to digital. Prior to that conversion, each time a dangerous goods movement took place, it meant manually filling out printed forms for government submission, a time-consuming process.

The solution was to move to a digital system where submission could be made through pre-completed web forms.

After spending four years developing that digital system, Dumitrascu brought that knowledge to the national level for Transport Canada and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

As she and TerraHub try to work their magic on the local level, Dumitrascu admits that acceptance at national or global levels must involve more than that.

As she has learned, the agricultural industry tends to do what the major corporations dictate. If agricultural giant, Bayer AG, wants transparency, there will be transparency in the agricultural sector.

“If I had the opportunity to address a major industry influencer, I would present my argument to Bayer this way: could there be greater adoption or consumption of your product if you could prove to your consumers that what they are consuming is better than your competitors?”

What is Blockchain?

Let’s start by saying it’s complicated.

The technology first entered the public eye in 2008 with the release of Satoshi Nakamoto’s whitepaper, Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System.

Although the term blockchain became synonymous with Bitcoin, it became apparent through the next few years that blockchain was not limited only to tracking and confirming the movement of Bitcoin as a currency. This realization took place partly because Vitalik Buterin – who had originally helped to develop the Bitcoin coding – published his own white paper propounding that a blockchain platform should be applicable to many different areas other than cryptocurrency.

And Buterin went on to launch a platform with those very same capabilities.

Launched in 2015 under the name Frontier (eventually evolving into Ethereum) it supported its own cryptocurrency called Ether, which can be applied to many sectors such as finance, insurance and manufacturing.

And, just as Bitcoin and Ethereum are cryptocurrencies that employ two different types of blockchain, blockchain itself is really a type of Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT).

Here’s where it can get a little confusing.

There is a distinction between the two technologies in that DLT is a decentralized database which is distributed across computers, also known as nodes. Updating takes place independently at each node. In blockchain, every node receives its own copy of a ledger and each time a new transaction is added, all copies are updated as a continuously growing list of records or chains of blocks.